Get Irish off life support and into real life, says JASON WALSH

THERE IS nothing as likely to start a wordy fight on the green ink pages of the Irish Times as the state of the Irish language. Into this fine tradition, forth has now waded knee-deep.

Writing in forth this week, Concubhar Ó Liatháin took issue with the bizarre new policy of the weekly newspaper Gaelscéal: giving priority to press releases published in Irish.

Ó Liatháin, of course, is the former editor of the late Irish daily Lá Nua so there is a chance that his criticism will be dismissed as sour grapes. The thing is, he’s right: Irish needs to be treated seriously as Gaelscéal no doubt wants but the newspaper’s policy will have the opposite result.

Gaelscéal has done the public a service in raising the issue of political parties’ hypocritical stance on Irish but giving undue preference to small parties simply because they publish in Irish is a retrograde step and is itself in line with the litany of linguistic policy missteps Ireland has seen down the years.

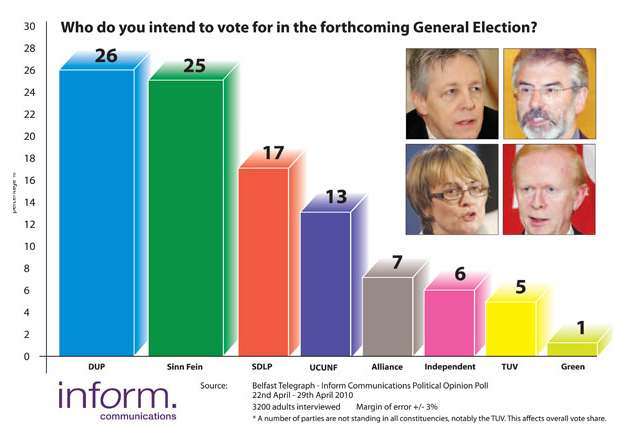

As Gaelscéal points out, only two parties regularly issue material in Irish: Sinn Féin and Éirígí.

Éirígí is a small left-republican outfit and, truth be told, does deserve more coverage—especially given that what little coverage it has had has been tendentious and relentlessly negative. Still, it is a minor party and should not be able to dominate political coverage simply by sending out e-mails as Gaeilge.

Sinn Féin is not a minor party, no matter what the Irish press likes to imagine, and its commitment to the Irish language is second to none. If the other parties followed Sinn Féin’s lead it would make life a little easier for Irish language journalists but this is not an issue worth picking a fight over. What matters is the content of a statement, not the medium it is issued in—something that applies as much to newspapers as much as it does press releases. Marshall McLuhan was wrong: the medium is not the message, the message is.

There is a broader issue at stake here: what do we actually want to do with Irish?

The gaeltachtaí are not actually a success—yes, they keep Irish alive but they also contribute to its marginalisation. Still, we’ve got them and there is no point in getting rid of them now. But that is no reason to blind ourselves to the fact that they do not represent the future of Irish. Because if they do, then the future of Irish is one of folk villages, tourists, píopaí and flat caps. Heritage Irish.

The Gleann Cholm Cille-Cill Charthaigh gaeltacht in County Donegal is in such an appalling state that people can now have a weekly visitor come to speak Irish at them. Paid for from public funds. Something is seriously wrong when the only form of conversation available is tantamount to state-aided prostitution.

Gleann Cholm Cille-Cill Charthaigh is an extreme example but it does illustrate the fact that for most Irish people the Irish language is not functional. Even the much-loved gaelscoileanna are as much about middle class parents getting a private-grade education for their kids at the taxpayers’ expense than any commitment to Irish as an actual medium.

What needs to be understood is that a language must serve a function over and above heritage, otherwise it may as well be left to die out, kept in existence only in old texts and university departments. If Irish was dead—and it very nearly was—there would have been no point in reviving it. As it happens Irish did not die, though it was certainly in a parlous state by the late nineteenth century. The Gaelic revival and later official efforts, one step forward and one step back, have got us as far as we are today—but sustaining the present is not good enough.

For Irish to actually be a meaningful language it has to be useful. Unfortunately this is precisely what Irish is not. Those who would like to see the language consigned to the dustbin of history, and there is no shortage of such people, regularly complain that no-one else speaks Irish, thus making it a ‘useless’ language. This is true but it is also irrelevant: the other official language, English, hasn’t gone away, you know… Making Irish useful is not achieved by encouraging the Belgians or Swiss to start speaking it for our benefit. Instead it should become a language of communication. Today it is used too often as a language that only communicates things about itself: writing about Irish, in Irish.

Gaelgoiri often come across as shrill and strident bores who do nothing but complain and make special pleading on behalf of the language they love to talk (about)—hence the nickname ‘gaelbores’. As with all caricatures there is at least a grain of truth in it, but understandably so. Gaelgoiri have every right to be pissed off and, like unionists, many of them recognise they are on the back-foot: Irish has rarely been taken seriously as a functioning language. Rather, it often seems to be promoted as a badge of authenticity and ‘Oirishness’. Suggesting people speak an cúpla focal doesn’t help—nor do regressive ‘you-can’t-live-here-English-speaker’ gaeltacht policies.

Successive governments and, it has to be said, language activists, have promoted Irish as a language fit only for poetry and road signs. Whatever lyrical qualities Irish may have are secondary to its use as a method of communication.

State aid for Irish includes the funding of the aforementioned weekly newspaper, Gaelscéal, published by Eo Teilifís and the Connacht Tribune. The funding for this organ was awarded in circumstances that caught the attention of every Irish language journalist I know, but that is a matter for another day.

That Gaelscéal is now threatening to treat English language soruces of information as being of lesser importance is something that no newspaper journalist could ever countenance.

One can only conclude that Gaelscéal is, in fact, not a newspaper. Rather it is a magazine. The difference is not insignificant. From the Irish Times through Morning Star to the Sunday World, each and every newspaper has its virtues and are intended as universalising vehicles to allow the reader to navigate his or her way in the world. A magazine, on the other hand, has no such lofty claim and, therefore, no responsibility to universality.

This fact is underlined by an interesting fact unearthed by Pól Ó Muirí: ‘[T]he paper’s staff are not referred to as ‘journalists’ but as ‘soláthróirí ábhair’, literally ‘subject providers’.’ (1)

Commercial media in Irish is a tricky proposition. The audience is small, perhaps vanishingly so. On the other hand, there are some success stories, however limited.

The daily newspaper Lá Nua is now dead. Unsurprisingly because, as with the late Daily Ireland, the Belfast Media Group’s (BMG) idea of ‘commercial’ activity seems to be all too tied to receiving government handouts either through the dreaded ‘funding’ or through the back door in the form of state-mandated advertising. Not that BMG is in any way unique in this, the Guardian relies on revenue from public sector job ads in its Wednesday edition and even then its greener-than-thou pontifications are largely underwritten by the profits from AutoTrader magazine.

Nós (2), a youth magazine published in Newry seems to being doing a job of work and without receiving a bean in ‘funding’. Interestingly, Nós has set its face deliberately against ‘heritage Irish’.

The business news web site InsideIreland (3) is bilingual. It remains to be seen if publishers Adman can turn a profit but it has certainly been interesting to watch an Irish language publication run daily stories without sucking on the teat of government largesse.

It will not have escaped the attention of any industry insiders reading that all three of the aforementioned publications are based in the North. I shall leave it up to readers to draw their own conclusions on that matter.